Intramuscular Stimulation (IMS) vs Acupunture

At first glance, you may be inclined to think that intramuscular stimulation (IMS) is similar to acupuncture. While acupuncture and IMS may use similar needles, the techniques employed are completely different. In acupuncture, needles are inserted into areas that correspond to "meridians of energy" running throughout the body. Pre-mapped, standard insertion points are used to target different organs and systems. In IMS the physiotherapist must have a greater knowledge of human anatomy and biomechanics, as the assessment of movement and alignment is key in finding which areas to treat. Additionally, the therapist looks for changes in skin textures to hone in on specific areas of treatment. The pictures below demonstrate a few of these indicators. Picture one shows thin imprints left in the skin, more notably on the patient's left hand side and not on the right. Picture two shows pea d'orange and an inability for the skin to be picked up and rolled. Finally, picture three shows goosebumps. All of these examples are used by your physiotherapist as indications of underlying dysfunction, including excessively tight muscles and inappropriate nervous system input.

IMS treatment involves inserting a very fine needle into affected areas of the body, without injecting any substance. The needles are inserted at the epicenter of taut, tender muscle bands, which can be found in the extremities or along the spine.

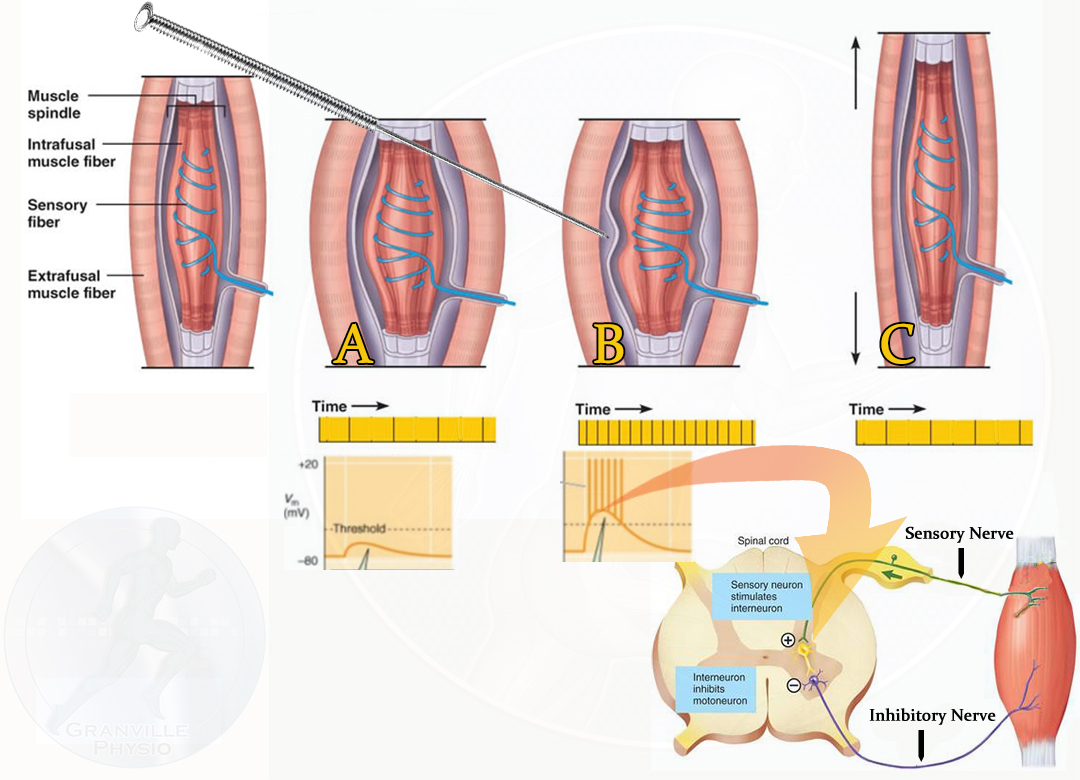

Penetration of a normal muscle is painless; however, a shortened, "tight" muscle will ‘grasp’ the needle in what can be described as a cramping sensation or a twitch. The result is threefold. Firstly, a stretch receptor in the muscle is stimulated, producing a reflex relaxation (lengthening), which then resets the muscle to a new resting length. Secondly, the needle also causes a small injury that draws blood to the area, initiating many natural healing processes. Finally, the treatment creates an electrical potential in the muscle, to make the nerve function normally again.

Penetration of a normal muscle is painless; however, a shortened, "tight" muscle will ‘grasp’ the needle in what can be described as a cramping sensation or a twitch. The result is threefold. Firstly, a stretch receptor in the muscle is stimulated, producing a reflex relaxation (lengthening), which then resets the muscle to a new resting length. Secondly, the needle also causes a small injury that draws blood to the area, initiating many natural healing processes. Finally, the treatment creates an electrical potential in the muscle, to make the nerve function normally again.

In the picture above you can see that a tight muscle (muscle A) causes a muscle spindle to send signals down the sensory nerve to the spinal cord at a rate below a certain threshold. This results in no excitation of the interneuron that connects to the inhibitory nerve in the spinal cord. In the muscle that has a needle inserted a twitch occurs (muscle B). This twitch causes the muscle spindle to send many signals down the sensory nerve that stimulate the interneuron which in turn stimulates the inhibitory nerve. The inhibitory nerve, in turn, sends many signals to the muscle telling it to relax. Muscle C is the new lengthened muscle. It will stay at this new muscle length until it is given another reason not to (such as poor posture causing a neck muscle to tighten).

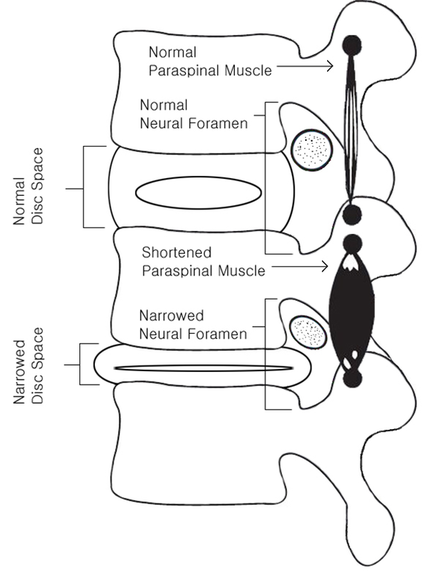

Typically the therapist will start with treatment of the affected spinal segment, and then move into your extremities. The reason for this is that dysfunction along the spine often causes increased pressure on nerves as they exit the spine. This increased pressure causes the nerve to be stimulated which leads to any muscles innervated by this nerve to become taut, even at rest. As an example, think of compression in your low back. While potentially just experienced as a stiff back, it can also cause a nerve to excite the muscles of the calf, and therefore may possibly be one of the causes for achilles tendon pain or calf tears/strains. In addition to this, the muscles innervated by a compressed nerve tend to be weaker than normal. This is for two reasons; fatigue from being stimulated all the time, and a limited ability to transmit signals down the nerve (think of a garden hose that has a kink in it, not being able to send as much water to the end of the hose).

The goal of treatment is to release shortened muscles, which can irritate and put pressure on nerves, among other things. Super-sensitive areas that have been created from chronic tightness in muscles can be desensitized, and the persistent pull of shortened muscles can be released. IMS is the most effective way to treat the underlying, "root cause" of a condition that causes pain and has spinal involvement. It is quite rare for an injury without any spinal involvement or reoccurring stress to last a prolonged period, making IMS a valuable treatment option in a wide variety of injuries.